Why Gender Inequality Still Exists in Hollywood

While everyone pretends to care, very little has changed.

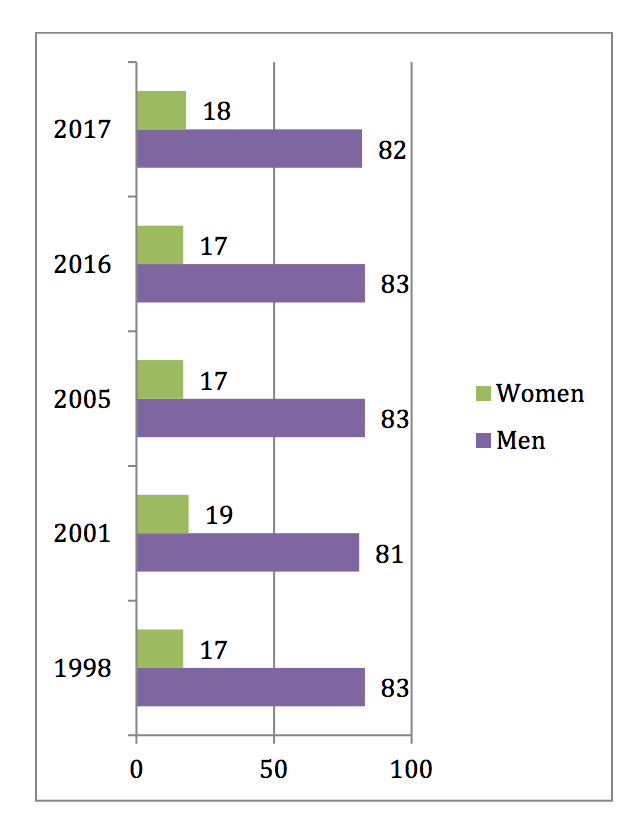

Of the top 250 grossing films of 2017, women comprised 18% of all directors, writers, producers, executive producers, editors and cinematographers. On the other side of the camera, only 24% of those movies had female protagonists. That’s 5% less than in 2016. But this is no news for anyone anymore, although it astonishingly feels like it.

Now that the Weinstein scandal has paved the way for some serious clean-up focused on men who for decades have abused their power in Hollywood, women in show business are, at long last, getting their voices heard to boost a movement they hope will create a better future and more opportunities for female workers in the industry.

#MeToo, Time’s Up, all-black dress code, passionate speeches,… The wind of change was hard not to sense during this year’s award ceremonies. Personalities like Seth Meyers, Jimmy Kimmel and Oprah, of course, didn’t miss a chance to refer to the many sexual harassment revelations that have and keep coming to light. But while it’s all refreshing and emancipating, inequalities in Hollywood between men and women remain at a standstill.

During those almost-political ceremonies, circumstances regrettably didn’t quite match the climate. At the Golden Globes, while Lady Bird was nominated for Best Motion Picture Musical or Comedy, its writer and director Greta Gerwig was nowhere to find in the – as sharply indicated by Natalie Portman during the show (not everyone liked it, but she was still damn right) – all-male Best Director’s list of nominees. To this day, only one woman has actually won the title. It was in 1984, when Barbra Streisand took home the prize for Yentl. 34 years ago…

As in the history of the glamorous Oscars (whose jury is 77% male), in the just 4 female filmmakers who have been nominated for Best Director, only one has won (Kathryn Bigelow for The Hurt Locker in 2010). And if you think things are a little easier for actresses, you might want to think again.

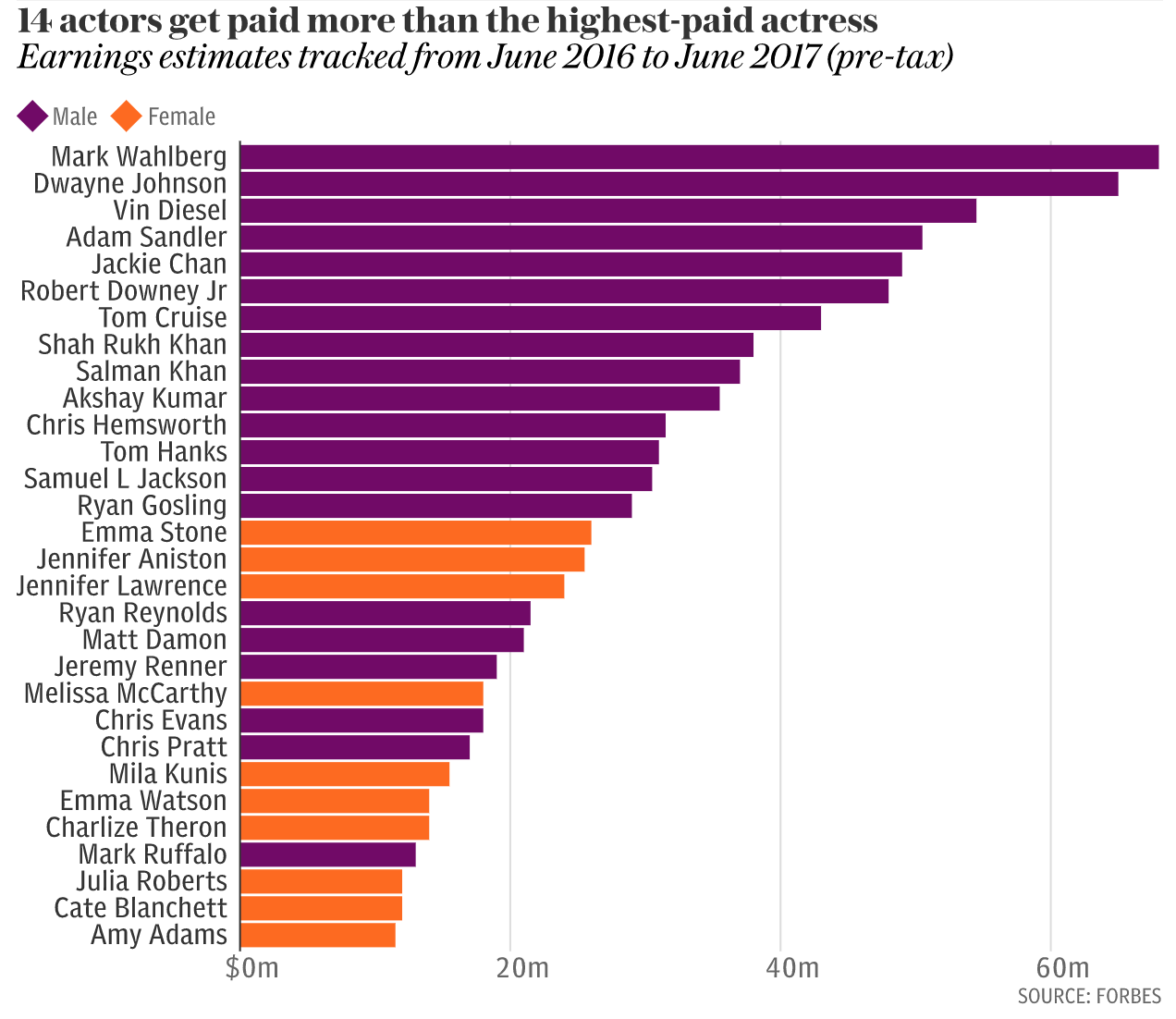

In 2017, Forbes published a report of the highest paid Hollywood performers topped by 14 (!) male actors, revealing that even the highest paid actress on the list, Emma Stone, earned more than 60% less than number one Mark Wahlberg ($26 million vs. $68 million).

While in the past 20 years the wage gap has narrowed in the U.S., with men the new minority in college graduates, it has not improved in the cinema industry since the ’90s.

With all sorts of new revelations about considerable salary disparities between stars like Wahlberg and Michelle Williams for All the Money in the World, or Claire Foy and Matt Smith on The Crown adding up to the growing number of reports of abuse in the workplace and open statements from celebrities like Jennifer Lawrence, Emma Watson, or Jessica Chastain, we have never talked about gender inequality in Hollywood more than today. So why haven’t things changed by now?

A Men’s World?

Sociological studies have shown that sexual harassment and discrimination is more likely to happen in a male-dominated industry. So, when another recent research from the University of Southern California revealed that women remain underrepresented in films (both on- and off-screen), with the majority of female characters younger than the males and not central to the plot, there was no reason to be surprised. Worst of all, a lot of stereotypes were reported when movies addressed sex, emotional and achievement topics, often portraying women using languages associated with conservative family values. If cinema is “a reflection of life”, we’re all screwed – Hollywood deeply functions as a White, straight boy’s club…

To understand how we got to this point, we have to travel back to the very birth of the movie-making business, when the gender dominance was, in fact, completely opposite.

During the early years of cinema, women actually prevailed in many areas of the industry. In 1916, the highest-paid director was 37-year-old Lois Weber, who shot 18 films just that year. Throughout the silent era, women wrote the majority of all movies, and the heads of editing departments were almost entirely female. Women leaders founded production companies and actresses topped the list of best-paid performers. As for writers, Frances Marion was the the first to win 2 Academy Awards and one of the most successful screenwriters between the ’20s and the ’30s.

At the time having their names attached to the new medium was not something actors wanted (shocking, we know), so in 1910, the most popular performer in America was only known as ‘The Biograph Girl’. Following her growing success, Florence Lawrence finally revealed her name and in the meantime initiated the star system, as by 1912, she became the highest-paid movie worker.

Between 1917 and 1923, women were more powerful in cinema than in just about any other business. Then came sound.

With the emergence of the ‘talkies’, commercial conditions drastically changed. While no real hierarchy had been previously established, once the industry was unionized, women became rapidly excluded. In 1934, the Hays Code (or Motion Picture Production Code) was passed, setting new rules on what was acceptable and what wasn’t in the industry’s content produced for U.S. audiences. That code, initiated by Will H. Hays, first chairman of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), remained enforced well into the late ’50s. By then, roles offered to women grew to be more conform to feminine expectations, challenging gender norms considerably less. Films followed more standardized depictions of love, marriage and family guidelines, leaving very little space for disruption of the status quo.

Despite its revocation in 1968 – instead replaced by the movie rating system – the Hays Code had set new norms for women in front and behind the camera. Consequently, its legacy impacted the industry and audiences’ expectations, shaping a world where it became common practice not to give a woman too much significance in favor of male predominance, cultivating stereotypes and discrimination.

About 50 years later, in 2015, Martha M. Lauzen, executive producer at the Center for Study of Women in Television for San Diego State University reported that the percentage of female-speaking roles in cinema has remained the same since the ’40s (between 25% and 28%)…

“The fact is – women are seriously underrepresented across nearly all sectors of society around the globe, not just on-screen, but for the most part we’re simply not aware of the extent,” stated actress Geena Davis, founder of the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media. “And media images exert a powerful influence in creating and perpetuating our unconscious biases.”

The Real Problem

Many, whose perception of women has unquestionably been defined by the way media and entertainment content reflect society, believe that the reason why they remain such a minority in movies is because viewers are just not interested in seeing female leading roles (despite women amounting to 50% of tickets buyers). A sad observation demonstrating that change can only come from the real source of the problem: not women, but those who lead Hollywood, as the situation will only truly change when they decide to.

All the recent revelations regarding abuses of power by high-ranking men in the industry and the actions taken as a consequence might show a shift in the right direction, but what’s known in the limelight doesn’t necessarily operates the same way behind closed doors.

For a long time, society and show business have established fears in women when confronted with gender discrimination. “It’s what we are conditioned to believe,” wrote Mila Kunis in a 2016 essay. “That if we speak up, our livelihood will be threatened; that standing our ground will lead to our demise.”

Today, we can fairly say, “Time’s Up.”